In spring of 1874, in the hills of Williamsburg, Massachusetts the large reservoir on the Mill River was filled to capacity. An earthen dam commissioned by mill owners held back a staggering amount of water: nearly 600 million gallons. On the morning of May 16, 1874, dozens of mills filled with hundreds of workers as they did any other Saturday. While workers were settling in in front of their machines and families were eating breakfast, the dam gave way. The overseer of the dam saw the initial break and rode bareback to alert the townsfolk in the center of Williamsburg. Within minutes, a roaring wave of water 30 feet high raced through the four mill towns: Williamsburg, Skinnerville, Haydenville, and Leeds, before dumping the contents it gathered in its rampage through the villages onto the Florence meadows. All told 139 people were drowned that morning.

The disaster captured the attention of the nation. Newspapers covered the calamity extensively. It had all the elements of a great story – victims, villains, and heroes – four men who raced by horse downstream, just ahead of the flood waters, to warn the people in the villages. They were given gold medals.

The telegraph and newspapers spread the news of the flood quickly in 1874, but word of the flood took 135 years to reach me.

I still am surprised when I say this: a nonfiction history book I read in 2009 literally changed the direction of my career. As part of a workshop on waterpower in New England, Elizabeth Sharpe presented her book on the Mill River flood. I was transfixed.

In particular, the spare but compelling accounts of women, whose job it was to identify and prepare the dead, haunted me. What if I wrote a book about tone of them, a mill girl? What if it was 1873 and a young girl wanted more freedom? And what if there was an opportunity to work in a mill that was safe and reputable? And what if that mill happened to be downstream from a faulty dam? What if taking your only opportunity for independence meant living with the threat of flood every day? And what if that dam gave way?

Answering these questions led me to my protagonist, a mill girl. Like so many of the real-life women before her, Catherine Bardwell would be seeking independence and some extra income before settling down to marriage.

This is where the story stalled, because I ran into my first problem.

I had no idea how to write historical fiction. I was writing, sure, but it was a draft of a contemporary YA realistic novel? I was no history expert. I didn’t know if this was my story to tell.

It was a stroke of good luck that my Writing I instructor wrote historical novels. Jeannine Atkins encouraged me to follow the urge to try historical fiction, to see if those unanswered questions could lead to a narrative. Not only that, she wrote in verse! By the end of 2012, I was fully committed to the form – historical fiction in poetry.

Then, the writing stalled again.

I didn’t know where Catherine would live or work. I mean, I only had the choice of four villages. How hard could it be to decide?

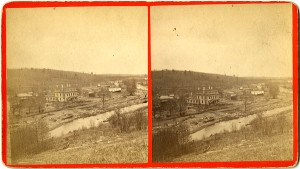

In fact, it was more difficult than I’d imagined. I researched all the different mills that existed – buttons, wool, brass – but then this picture really convinced me to place Catherine in Skinnerville. Of the four villages, Skinerville was most thoroughly erased. Only one building stood: Skinner’s mansion, a symbol, I thought, of the divide between mill owner and worker – a physical depiction of class and capitalism that echoed some of the themes I’d been exploring in my writing.

And then there was Mr. Skinner. Her relationship with him is the core of the book. Placing Catherine in Skinnerville and having her develop a relationship with Mr. Skinner was the key to unlocking this story. Shortly after making that decision, I wrote a first draft of the novel.

This fall, things really picked up pace. I took a leave from my teaching job so I could devote myself to graduate school and this project. As part of my MFA mentorship, I worked with Katie Cunningham at Candlewick. The first thing we did was take that first disaster of a draft and restructure the novel (her first major revision note: don’t lead with the disaster!).

Just as I was completing my first revision for her, a friend told me about the Highlights Foundation Whole Novel Historical Fiction workshop. I applied for and was accepted into the group and given the scholarship I needed to attend. More importantly, my ever patient spouse agreed to take the five children for an entire week!

The Highlights retreat was an amazing opportunity to immerse myself in a community with 16 other people who care deeply about and are fully committed to this sub-genre: historical fiction for young people. I was privileged to work with Linda Pratt, an agent with an eagle eye for writing craft, and we had many conversations about writing in general and Fly to the Hills in particular. If you’d let me, I would spend an hour sharing all the practical tips and tricks that I learned from her and the other faculty members.

Now, my time at Highlights became another turning point for this novel.

Working with Linda and the other faculty members helped me understand two things. First, that I needed to embrace the fiction part of the novel. Second, that composite characters and a solid author’s note could free me from the bounds of “true history.” One day at highlights, I was talking over some plot points with Linda, and I said, “I think Skinner would offer this, but Catherine wouldn’t agree to that,” “Of course not,” Linda said. “You would know. She’s your character, after all.”

This fall has given the opportunity to reflect on myself as a writer. I write character-driven stories. And what I found out this fall, was doing it in historical fiction was really no different. Start with a character, put her in a setting, and give her challenges to face.

I like to think that the manuscript is not quite such a disaster now. Karen Hesse said “Once I knew it was my story to tell, there was no turning back.” It took four years to come to that understanding, but now I believe that know: this is my story to tell, and I can’t wait to share it with readers.